Rating: 4 /10

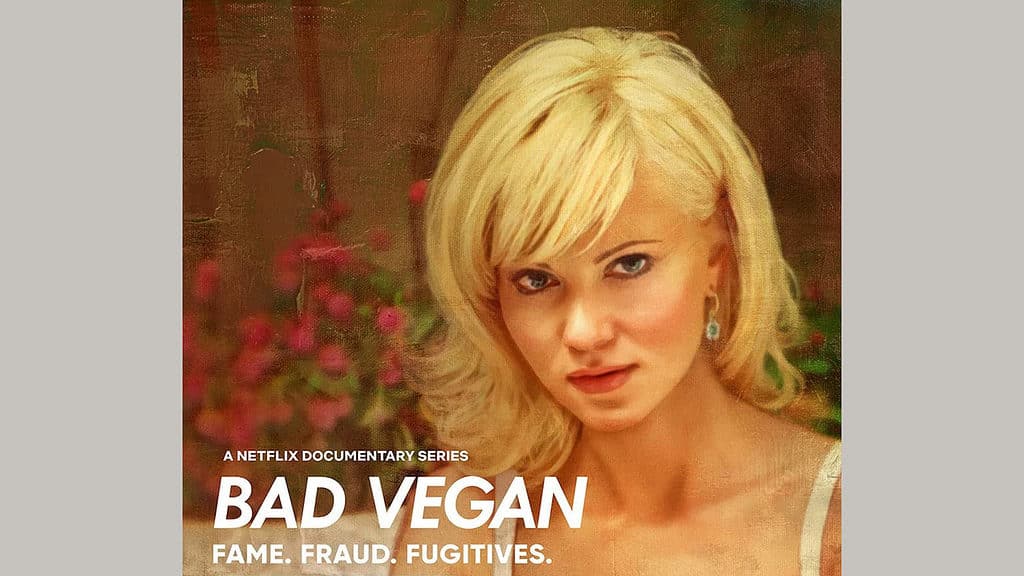

True crime as a genre often exploits the pain and trauma of victims. The Netflix series Bad Vegan: Fame, Fraud, Fugitives makes some effort to undercut the usual misogynist impulse to blame the targets of domestic abuse for the harm done to them and others. But ultimately director Chris Smith is swayed by the appeal of easy scandal and smug both-sidesism.

The title is a telling failure in itself. As the series itself acknowledges, people resent vegans, and see them as superior elites who look down on others. Everyone wants to catch a vegan out in hypocrisy.

That was a big part of the tabloid attraction of the story of vegan cook and restauranter Sarma Melngailis in the first place. The narrative Smith finds himself with isn't really about Melngailis' iniquity. But he kept the title because he knew it would draw people in, even at the expense of doing further harm to someone who had been plenty harmed already.

Abused Vegan

As those paying attention to headlines back in 2016 may remember, Melngailis was a successful New York restaurant owner and cook. She was best knonw for her vegan raw food restaurant, Pure Food and Wine, opened in 2004 with her then-husband chef Matthew Kenney. Starting in 2007 she also ran takeaway retail vegan store One Lucky Duck.

Melngailis is attractive, and her restaurants were very successful. She became a hip New York figure and brand, with great cache in celebrity circles. She seemed to have a bright future.

But then, to her great misfortune, she met Anthony Strangis. Strangis was a compulsive gambler and con-artist, who fed his habit by duping women into giving him large sums of cash. He courted Melngailis online and after he got close to her, embarked on a campaign of bullying and promises similar to cult indoctrination.

Strangis convinced Melngailis that he was wealthy and powerful, and that he alone could make her dreams of love and business success come true. All she had to do was trust him and give him money without question. They married and he took control of her email and social media accounts, as well as of her bank information. Under his coercion and manipulation, she ultimately drained her businesses of more than $1.5 million dollars, which he gambled away. He also contacted Melngailis' mother behind her back and defrauded her of $450,000.

As her business disintegrated, Melngailis was unable to make payroll. She couldn't pay taxes or investors. Eventually, Strangis took her on the run. When they were caught in Tennessee, tabloids and media wrote it up as if the two were Bonnie and Clyde. Much was made of the fact that they were caught after ordering an unhealthy Domino's pizza.

An attractive hip vegan is actually an evil con-artist and hypocrite: that's a fun and exciting piece of gossip. The truth-that a successful woman was abused and manipulated by some random jerk no one has every heard of -is much less headline friendly.

The Truth, Sort Of

Smith interviewed Melngailis extensively, and her voice drives the narrative. There are recordings of conversations between her and Strangis, and transcripts of emails between them. You get a sense from their interactions of just how vicious and manipulative he was. He bullied and insulted her relentlessly while promising that the misery and hardship would end with just one more big cash payment.

The deeper in he drew her, the less she could afford to believe she'd been duped, and that all that money was for nought. He even played on her love for her pit bull, promising he could keep the dog alive forever if she just obeyed him in all things. He also sexually abused her, though the documentary spends a lot less time on that than on the dog immortality.

The film provides a good bit of corroboration for Melngailis' story. Strangis' former wife talks about how she was deceived and controlled by him. There's evidence that Strangis did in fact access her online accounts, and would sometimes send emails as her to friends and business associates. The police even confirm that Melngailis didn't buy or eat the stupid pizza.

And yet, Smith is very reluctant to fully accept what his own documentary is telling him. Especially at the close of the four-episode series, he plays up doubts. Some of Melngailis' former employees and business associates, say she was too smart to not understand what was happening. They say she has responsible for her choices-choices which led to immense financial hardship for those who worked for her and trusted her. Why didn't she cut Strangis off? Why didn't she ask for help? Why didn't she call the police?

Me Too

These kinds of objections have become familiar from discussions of sexual workplace violence after the #MeToo movement, which started just a little too late to be of help to Melngailis.

As we've (hopefully) learned from those conversations, victims of abuse are often afraid to leave because they worry it will cause their abuser to escalate. They may feel so disempowered that they think no one can help them. They may feel shame, and think everyone will blame them since they blame themselves. They may worry that the police will be unsympathetic or may take their abuser's side.

Nor are these fears unrealistic. Police, after all, arrested Melngailis; she was convicted and served several months in prison.

Smith could have interviewed experts on domestic violence or cult indoctrination; he could have mentioned #MeToo. But he doesn't. Instead he ends the series with an apparently cheerful phone call between Melngailis and Strangis in 2018. It suggests that they were colluding, or at least had an ongoing relationship.

In fact, though, as Melngailis wrote in a blog post after the series was released, the recording was made specifically to trap Strangis for the documentary. She was not in touch with him, and she sounds conciliatory because she was trying to get him to reveal information. Why not just say that? Why make it look like she's the bad guy, or might be the bad guy?

The answer seems clear enough. Malengailis is more valuable to the documentary makers as a bad guy, or as an ambiguous figure, than she is as a victim of abuse. Deceitful women and bad vegans are racy and exciting; they pull people in. You love to hate them.

There's maybe someone to hate in Malengailis' actual story. But there's not a whole lot to love. The truth is that the series is not much fun to watch. The abuse Malengailis underwent is miserable to experience, even secondhand, and there's no justice or accountability. Strangis destroyed her life, served a year in prison, and then trotted off to scam someone else. Meanwhile Malengailis' life is still destroyed. Some people in the press, like Chris Smith, may have benefited. But after watching Bad Vegan, it's hard to feel good about that, either.

Bad Vegan is currently streaming on Netflix.

Terrilyn Ryan says

Once upon a time networks reviewed ethical content of productions in order to provide evidence of accountability to the public. Netflix lacks peer review Before televising. Like Chris Smith, Netflix only wants the clicks, leaving truth optional.

Nice research. Thanks